Acute Cervical Spinal Cord Infarction (FCE) in a St. Bernard

Diagnostic Imaging

A 4-year-old, male, neutered St. Bernard presented to a local emergency hospital for acute right thoracic limb lameness and was unable to place weight on the affected leg. The emergency hospital conducted a thorough examination, work-up, and determined an underlying neurologic process was likely the cause for the patient’s lameness and referred him to the GCVS Neurology Department.

Once the patient was placed in the care of the GCVS Neurology Department, they confirmed through their neurologic exam that the patient had a right thoracic limb monoparesis. The differentials for the patient’s acute lameness were an acute non-compressive nucleus pulposus extrusion (ANNPE), fibrocartilaginous emboli (FCE), lateralized intervertebral disc extrusion, or neoplasia. It was determined that an MRI would help to differentiate these possible causes and help guide treatment. A cervical MRI was ordered and acquired the same day by the GCVS Diagnostic Imaging Department.

MRI and Diagnosis

The patient was placed under general anesthesia by the GCVS Anesthesia Department for his MRI. The MRI was acquired in multiple planes, with and without contrast. The MRI was read by a GCVS Radiologist. A lesion was identified within the caudal cervical spinal cord.

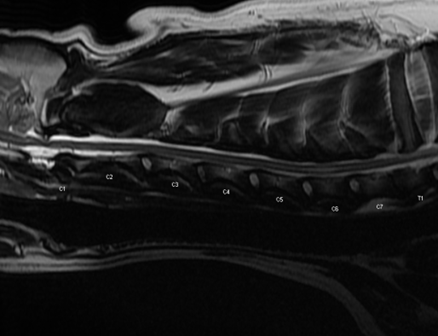

In the sagittal T2-weighted image below, there is a central hyperintensity within the spinal cord centered over C6. This lesion was isointense on T1w and did not contrast-enhance.

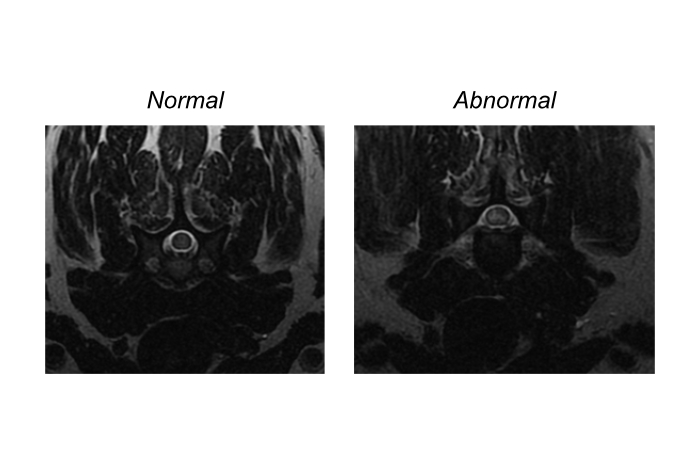

In the transverse T2-weighted images below, the patient’s normal spinal cord is visible in the left image and the lesion in the patient’s spinal cord is shown on the image on the right. The parenchyma of the normal spinal cord is relatively homogeneous and is slightly hyperintense to muscle. However, on the affected portion of the patient’s spinal cord, in the right image, you can see a marked hyperintensity that affects the right side of the spinal cord, predominantly the gray matter. (Reminder: MRI images are displayed with the patient’s right on the viewers left, and the patient’s left on the viewers right).

These MRI findings are most consistent with a fibrocartilaginous emboli (FCE) diagnosis:

Lesion is not centered on an intervertebral disc space, but may be near a degenerative disc.

T2-weighted sequences identifies fluid accumulation or edema in the spinal cord (hyperintense lesion), that is realtivly well defined, mostly affecting the grey matter, and usually lateralized or asymetric.

Possible swelling of the spinal cord causing attenuation of the subarachnoid space signal.

T2* sequences help identify hemorrhage if present.

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) can detect infarction as early as within one hour of the onset of clinical signs.

About Fibrocartilaginous Embolism (FCE)

Fibrocartilaginous embolism (FCE) is a vascular disease of the spinal cord caused by embolization of the spinal vasculature. The embolic event leads to ischemic necrosis of the region of the spinal cord that depends on blood flow from the affected vessel. Onset of neurologic dysfunction is peracute, often occurring suddenly during activity such as running, jumping, or playing, and clinical signs are frequently asymmetric. Many dogs will vocalize at the onset of the event, suggesting initial pain, although this pain typically subsides quickly.

Neurologic dysfunction from FCE is generally nonprogressive within 24-48 hours following onset. The condition is most commonly seen in large and giant nonchondrodystrophic breed dogs, and the most frequently affected spinal segments are C6-T2 and L4-S3.

Treatment and Recovery

Treatment for FCE is conservative and focused on supportive care. Nursing care and physical rehabilitation are essential to recovery. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic medications may be administered if spinal hyperesthesia is present.

This patient remained in the hospital to help monitor his recovery, given his large size. His clinical signs did not progress and remained stable for 48 hours. Within 72 hours, he was able to get up on his own and take a few steps with support. He was discharged and medically managed by the GCVS Neurology Department. The patient continued to improve and was able to walk unassisted within 72 hours of returning home.

Successful outcomes in dogs with FCE are closely related to the severity of neurologic signs at presentation. On average, dogs regain voluntary motor activity within 6 days, walk unassisted within 11 days, and reach maximal recovery by approximately 112 days.